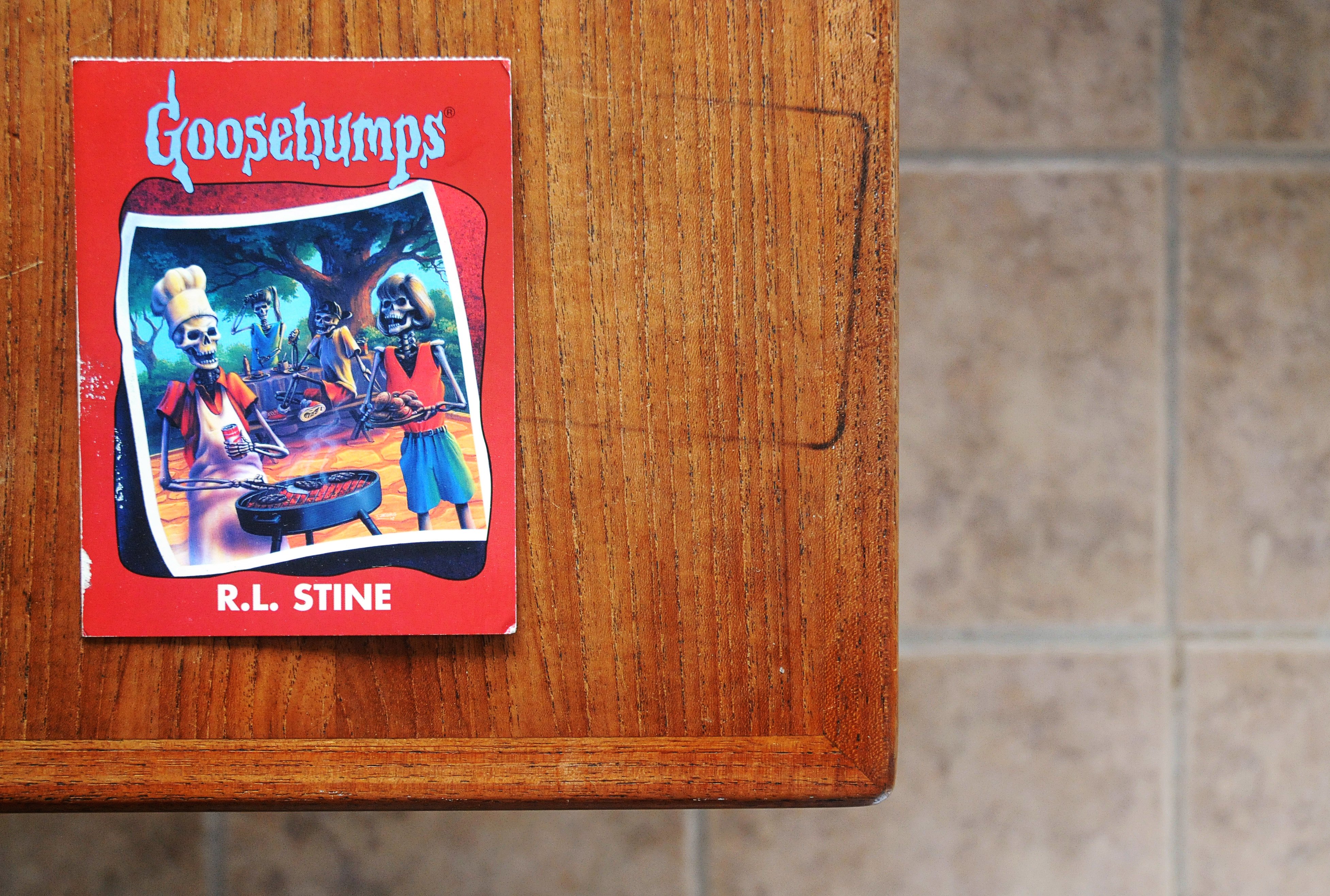

If someone told me as a first-year, school-based SLP that a “Goosebumps” novel would teach me a powerful lesson about inclusivity and friendship, I would have told them I have an IEP meeting at 3 and to kindly move out of my way.

When I attended a book fair several years ago, most of my students entered the fair apprehensively but soon took an interest in the books their typical peers were buying. The revolving display of “Goosebumps” novels attracted considerable attention. A teacher pulled me aside to explain that most special education students wouldn’t be able to read or comprehend books independently. I could only imagine my students' frustration when they were directed away from the books they wanted and persuaded to choose something less appropriate for their age.

A week later, I returned to the teacher with a proposition. We would try a push-in therapy program centered on “Goosebumps.” We would read aloud together with key vocabulary and concepts reviewed before and after each chapter. We would track story grammar on a visual organizer and make predictions throughout our sessions. Character dynamics from the story would start conversations about our own experiences. The teacher reminded me she was concerned about students’ social skills and worried they might struggle with sustained attention during our sessions. I assured her the kids would benefit from engaging with this motivating content while I quietly maintained concerns that my plan might end in disaster.

By December, we were closing in on our final chapters. Students who struggled with participation now raised their hands to offer predictions and opinions, which were often met with “I told you so” or “no way” responses from peers. Others began picking up on the nonverbal cues offered by the large group setting and improved their ability to recognize emotions, hyperbole, and metaphor with less adult support. Most importantly, students began to bond with one another over their shared enthusiasm for the novel. This fostered more positive interactions in speech therapy and sparked genuine friendships between some peers.

By the end of the year, every student in the class could name and describe one or two close friendships in their own lives. Classroom teachers were pleased to see the students receive compliments and social bids when they carried their novels around campus. In one instance, our PE teacher observed one of my students ask a neurotypical peer about his “Goosebumps” t-shirt during class.

While I expected skepticism from parents during IEPs, most appreciated how much time we spent working toward authentic interactions rather than discrete skills or scripted conversation. Several families were eager to implement similar adapted reading strategies at home.

A growing body of neurodivergent activists, researchers, and their allies have worked to validate the importance of mutually motivating interactions as the basis for meaningful friendships. It is worth all of the time and thoughtfulness we can spare to understand our clients, identify and foster their interests, and, most critically, help them connect with others who share those interests. Your results might be scary good!

Author: Teadora Taddeo, M.S., CCC-SL